After a year of Trump, who are the winners and losers from US tariffs?

- Written by Prachi Agarwal, Research Fellow in International Trade Policy, ODI Global

During the 2024 presidential campaign, Donald Trump promised to ease economic pressures on households and restore US economic strength. Central to that promise was the claim that tariffs would revive manufacturing and rebalance trade in America’s favour. Once in office, the second administration quickly made trade policy – especially tariffs – a central pillar of its economic agenda.

The introduction of a sweeping tariff regime[1] on April 2, framed as “reciprocal tariffs”, became the signature economic intervention of the administration’s first year in power – and it appears we have not heard the last of it.

The tariffs were not a single event but a sequence of trade actions launched immediately after Trump’s inauguration. In January, the administration announced the “America first” trade policy[2]. This prioritised reductions in the US trade deficit to revitalise domestic manufacturing and promised tougher economic relations with China. Sector and country-specific tariffs followed.

While Trump’s so-called “liberation day” in April set the stage as he announced a range of tariffs to levy against various countries with which the US was running a trade deficit, the implementation was delayed until August, creating prolonged uncertainty for firms and trading partners.

The tariff regime pursued three objectives: raising government revenue, reducing the US trade deficit, and compelling changes in China’s trade behaviour. But one year into Trump’s second term, has this strategy worked?

What worked

On revenue, the policy has delivered. Customs revenue rose sharply by US$287 billion (£213 billion)[3], generating additional fiscal revenue outside the normal congressional appropriations process. In headline terms, the tariffs achieved what they were designed to do: they raised money – but mainly (96%) from American buyers[4].

Progress on the trade balance (exports minus imports) has been far less convincing. Despite a modest depreciation of the US dollar and stronger export growth during much of 2025, the total US trade balance (goods and services) fell by US$69 billion[5]. While the deficit on the goods trade balance (without services) at times narrowed, there is no evidence that this will be a sustained trend.

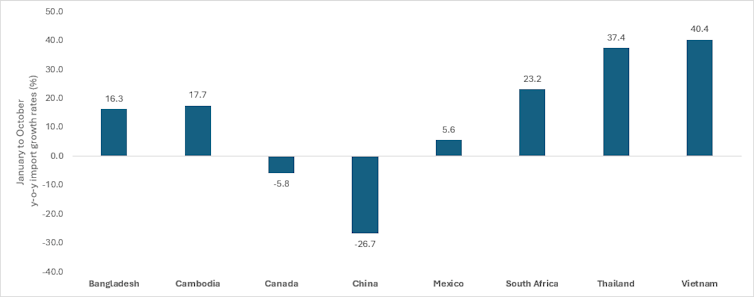

Addressing the trade imbalance with China is at the core of the Trump’s tariff strategy. According to trade data from the US Department of Commerce, during the first ten months of 2025, US imports from China declined by 27%[6] – the largest of all US trading partners bilateral decline observed. Tariffs on Chinese products were imposed immediately, without the transition periods granted to most other trading partners. On paper, this aligns with the administration’s objective of curbing Chinese market access.

But this contraction must be placed in context. US imports from China had already fallen by 19% between 2022 and 2024 amid rising geopolitical tensions and earlier trade restrictions. More importantly, China continues to post large global trade surpluses and has diversified both its export destinations and its product composition, reducing reliance on the US.

Rather than weakening China’s trade position, the tariff regime has accelerated supply-chain reconfiguration[7], as trade is now being trans-shipped through other countries before arriving in the US. Additionally, China has also increased trade with other countries that has replaced the reduction in US-China trade.

References

- ^ sweeping tariff regime (odi.org)

- ^ “America first” trade policy (www.whitehouse.gov)

- ^ rose sharply by US$287 billion (£213 billion) (www.richmondfed.org)

- ^ from American buyers (www.kielinstitut.de)

- ^ fell by US$69 billion (www.trade.gov)

- ^ declined by 27% (www.trade.gov)

- ^ accelerated supply-chain reconfiguration (odi.org)

- ^ US trade diversification intensified (www.trade.gov)

- ^ largely been passed through (www.reuters.com)

- ^ higher consumer prices (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ everyday goods (www.reuters.com)

- ^ rose by a meagre 1% in 2025 (www.federalreserve.gov)

- ^ vulnerability of low- and middle-income countries (odi.org)

- ^ US$89 billion annually (odi.org)

- ^ penalised economies (odi.org)

- ^ relied on labour-intensive manufacturing sectors (tessforum.org)

- ^ Women make up a large share of workforce (odi.org)

- ^ hit harder than men by the tariff measures (odi.org)

- ^ within days (www.reuters.com)

- ^ Section 122 (www.govinfo.gov)

- ^ linked to geopolitical disputes, such as Greenland (www.reuters.com)

- ^ risk of widening trade conflicts (www.ft.com)