Judas and the economics of betrayal

- Written by Renaud Foucart, Senior Lecturer in Economics, Lancaster University Management School, Lancaster University

No one remembers the names of the soldiers who arrested Jesus, or the civil servants who organised his crucifixion. But Judas Iscariot has not been forgotten, and will forever be associated with treachery and betrayal.

Part of what makes Judas stand out is his position as a disciple. There is only betrayal if there was some form of loyalty beforehand. And many of us will have felt the cruel sting of being let down by people we trusted – whether it was in politics[1], in the family, in a workplace, school playground or on a game show[2].

But on a more positive note, plenty of research suggests[3] that acts of betrayal are rare. Most humans can be trusted it seems, not because they are genuinely good, but because it is in their interests to be trustworthy[4].

One social science experiment about betrayal[5] involves a participant, referred to as “the sender”, being given a small amount of money. The sender can decide to keep the money for themselves, or they can choose to send it to someone else – “the receiver”.

If the money – let’s say £10 – is sent, it turns into £30. The receiver can then either keep the money or return half of it to the sender so that each ends up with £15.

The selfish prediction of what the outcome of this trust game might be is straightforward enough. We know that the receiver is better off keeping all the money if she receives it. The sender should expect that to happen, and not send the money in the first place.

But we also know that people do not always behave selfishly. And the many variants[6] of the trust game find that on average, half of the senders do decide to send the money – and that overall, enough money is returned to them to make sending a profitable decision.

So perhaps people return the money because they feel that doing otherwise would be a betrayal. And one possible explanation for this is the notion of reciprocity[7].

In this scenario, the receiver returns money because she believes the sender has been kind to her. Sending is a kind action because the sender does it without any guarantee of getting something in return. Returning some of the money is a way of reciprocating this act of kindness.

But research suggests that what actually seems to matter more[8] is a sense of guilt. The more the receiver believes the sender expected something in return, the more likely she is to return the money. In that sense, sending the money may be less about kindness, but about being a good investment.

In a recent experiment[9], a colleague[10] and I took the question a step further. We wanted to understand the roots of betrayal and how it might be affected by some form of shared experience.

In a slightly modified version of the original trust game, we asked both subjects simultaneously to send or keep £10. If at least one chose to keep the money, both got £10. If both sent the money to the other, one of them was picked at random and allowed to keep the £30 or share it equally.

Here, one might expect that even completely selfish people without any guilt aversion would choose to send money, simply because they can expect (around half the time) to get the larger sum of £30.

We ran our experiment in a garment factory in Pakistan, as we were inspired by a form of credit widely used in that country[11], in which[12] people combine their savings. They are then able to withdraw varying amounts from that sum of money to pay for things like sending a child to school or starting a small business.

The whole system relies on cooperation. If one person decided to betray their fellow contributors and run away with all of the money, it would be the end of the project for everyone.

Read more: Why Judas was actually more of a saint, than a sinner[13]

In our experiment, our subjects chose to share the £30 around 70% of the time, even more than the 55% who did so in the original trust game experiment we ran at the same time. Overall, we found that the initial option[14] to both send money creates a sufficiently large sense of loyalty to encourage further cooperation. This effect is higher when subjects were in a room of workers they knew – even if the actual co-player remained anonymous.

And maybe most of us have learned the social benefits of not betraying our fellow human beings. That’s why it’s fairly rare, and why stories of betrayal stand out.

Maybe Judas knew this too. And some people have decided to give him the benefit of the doubt.

The apocryphal[15] Gospel of Judas[16] for example, casts Judas as an Easter hero, without whom there would be no Christianity. And in his short story Three Versions of Judas, the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges[17] suggests that the disciple’s act was a vital part of a divine plan, which he carried out despite realising that in doing so he would become history’s ultimate villain.

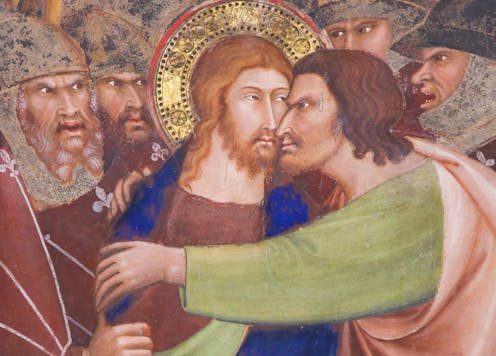

From that perspective, perhaps the kiss of Judas could come to be seen not as an act of betrayal but as the ultimate act of selfless cooperation.

References

- ^ in politics (theconversation.com)

- ^ a game show (www.bbc.co.uk)

- ^ plenty of research suggests (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ interests to be trustworthy (www.econstor.eu)

- ^ experiment about betrayal (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ many variants (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ reciprocity (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ seems to matter more (repec.unibocconi.it)

- ^ a recent experiment (link.springer.com)

- ^ a colleague (jhwtan.wixsite.com)

- ^ widely used in that country (academic.oup.com)

- ^ in which (www.jstor.org)

- ^ Why Judas was actually more of a saint, than a sinner (theconversation.com)

- ^ initial option (www.journals.uchicago.edu)

- ^ apocryphal (www.britannica.com)

- ^ Gospel of Judas (www.nationalgeographic.com)

- ^ Jorge Luis Borges (www.britannica.com)

Read more https://theconversation.com/judas-and-the-economics-of-betrayal-221813