Stock markets have been a one-way bet for many years thanks to the 'Fed put' – but those days are over

- Written by Edward Thomas Jones, Lecturer in Economics, Bangor University

The prospect of a Russian invasion of Ukraine have sent the markets into a tailspin, compounding fears around inflation that have been building over the past few months. The S&P 500 is trading at 10% below its recent all-time high, while the Nasdaq is down by over 16%.

The markets have been inflated for years by very easy monetary conditions in which interest rates have been ultra-low and central banks have been “printing money” in the form of quantitative easing[1] (QE). But one additional factor that has encouraged investors to put so much money into the markets is the so-called “Fed put[2]”. This is the idea that the US Federal Reserve (and other central banks) will not allow the markets to fall beyond a certain threshold – say 20% to 25% – before riding to the rescue with lower rates and more QE.

Such is the debt in the global financial system, goes the logic, that the markets cannot be allowed to fall any further. A bigger drop could set off a chain reaction of bad debts that could destabilise the biggest banks and cause a crisis that would make 2008 look mild.

Known as a “put”[3] in reference to a financial instrument that options traders buy to protect themselves from a fall in the markets, the argument is that markets are effectively a one-way bet. Certainly, the S&P 500 has risen sixfold since 2009 and the Nasdaq 12-fold as central banks have eased monetary conditions repeatedly. Even the under-performing FTSE 100 is up by two-thirds over the same period.

We would argue, however, that the Fed put no longer exists. Let us explain why.

The put in action

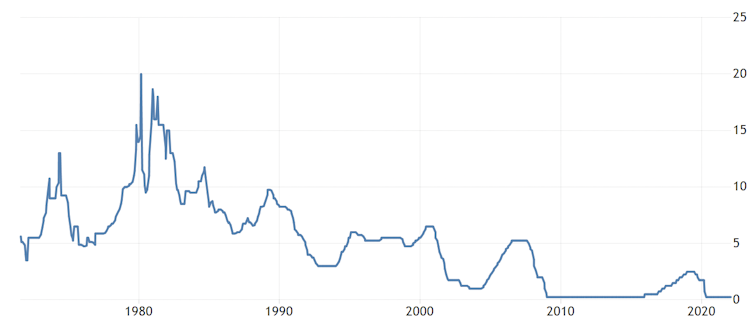

The idea emerged when Alan Greenspan[4] was chair of the Federal Reserve. Starting with the Black Monday crash of autumn 1987, Greenspan became known for cutting the federal funds interest rate to improve investor sentiment when markets dropped significantly. This was a big shift from the Fed’s previously very slow and cautious approach to changes in the business environment.

When Greenspan cut aggressively after the dotcom crash in the early 2000s, it helped to inflate the US subprime housing bubble that precipitated the 2007-09 crisis. During that crisis, the Fed’s response[5] – now under Ben Bernanke – was again to cut rates and also to increase the money supply through QE. This extra money encouraged financial institutions to lend to businesses and consumers to haul the wider economy out of recession, and lend more[6] to traders so that they could plough it into the markets.

Federal Funds rate 1972 to present