War is stopping Ukraine from paying its debts -- here's how international powers can continue to support its recovery

- Written by Matt Qvortrup, Chair of Applied Political Science, Coventry University

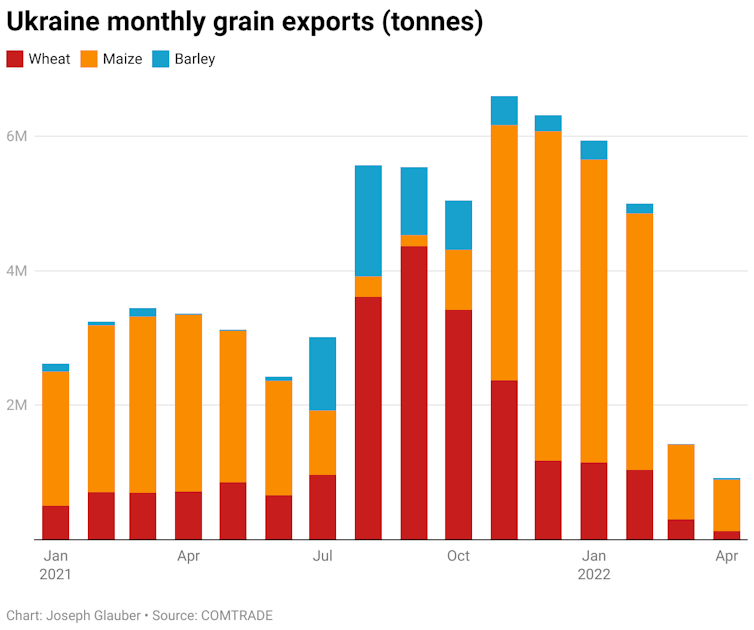

Ukraine is burning through money fast. The invasion by Russia has been costly for the country. According to the International Monetary Fund[1], Ukraine’s GDP could shrink by 35% as a result of the war. The country’s international grain exports[2] have been severely hampered, with a recent deal to restart exports likely to move only some[3] of its current stocks. The country shipped[4] US$27.8 billion (£22.6 billion) in agricultural products to other countries last year, or 41% of its total exports.

It is not surprising then that the country’s public finances are in distress. Ukraine’s ministry of finance has estimated its public sector deficit[6] increased from US$2 billion in March 2022 to as much as US$7 billion by May.

If Ukraine runs out of money it would not only affect the war effort, but could also leave the country unable to pay nurses, teachers and police officers, among other important workers. The negative implications of this for the people of Ukraine would be varied, ranging from the breakdown of important services to an inability for households to pay bills and buy food. This a significant concern of course, but the outlook is not as catastrophic as some might think.

Ukraine has already received funding from allies, with more promised. The US, for example, has committed approximately US$5.3 billion[7] in security assistance to Ukraine since the beginning of the Biden Administration, including around US$4.6 billion during “Russia’s unprovoked invasion”, the US Department of Defense says.

And this is not the only help received by Ukraine. The G7 and EU have announced[8] official financing commitments to Ukraine worth US$29.6 billion. EU leaders have also pledged additional support[9] of up to €9 billion (£7.6 billion), on top of a previous €1.2 billion emergency loan. This money from international partners will tide Ukraine over in the short term. So paying the interest on this debt and managing its upcoming bills will be not an immediate problem for Ukraine, although it remains a concern.

A more pressing challenge will be repaying its outstanding loans and bonds. With little money coming in, it will be hard for Ukraine to fulfil these obligations. Indeed, the country already asked for permission to freeze around US$20 billion in debt[10] earlier this month. This request was immediately approved by western governments, most notably Germany[11].

Another challenge for the Ukrainian economy right now is the continuation of the war – of course because of the ongoing negative impact on its people, but also due to the financial consequences. A prolonged war will only bring more uncertainty for the country’s economy. Major cities across Ukraine[12] are being hit by Russian missiles and there have been continued attacks on important infrastructure[13], including railways and ports. In addition to the short-term concerns around this, it also leaves little incentive to invest in the country at the moment, adding another long-term challenge to Ukraine’s economic outlook.

There is always the danger of a default, which is economist-speak for running out of money. And, in fact, Ukraine already defaulted on loans[15] in 2020. This was not a catastrophic event, but it raised interest rates on any new loans the country sought. Lenders are typically not keen to loan money if there is a risk they won’t get it back, but the political situation and the pronouncements of support by western powers discussed above means Ukraine is more likely to receive money to prevent another default. This kind of very public commitment means these governments are likely to be willing to continue to pay a considerable price to keep Ukraine afloat, both militarily and economically.

It is also worth bearing in mind that, as bad as the economic situation is for Ukraine, the Russian economy is suffering too, which could affect the length and outcome of the war. Reports that Russia has withstood the sanctions – that they “sting but do not cripple[16]” its economy – are inaccurate. This is the story the Kremlin would like us to believe, and is perhaps why Russia decided to no longer release data on key economic indicators[17].

A recent report[18] published by Jeffrey Sonnenfeld and colleagues from the Yale School of Management, points out that, due to business retreats: “Russia has lost companies representing 40% of its GDP, reversing nearly all of three decades’ worth of foreign investment and buttressing unprecedented simultaneous capital and population flight in a mass exodus of Russia’s economic base.” Add to this that the country’s foreign exchange reserves are diminishing at a startling rate – an estimated US$75 billion has been lost since the start of the war – and we get a more nuanced perspective of the true state of affairs.

The destruction, death and devastation experienced by Ukraine is only one part of this war, loss of livelihood is another. Governments opposing such invasions need to help economically as well as militarily. So far, western countries have done so for Ukraine, but this support must continue if its economy is to survive.

References

- ^ International Monetary Fund (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ international grain exports (www.ifpri.org)

- ^ only some (www.ft.com)

- ^ shipped (www.fas.usda.gov)

- ^ International Food Policy Research Institutute (IFPRI) (www.ifpri.org)

- ^ public sector deficit (gmk.center)

- ^ US$5.3 billion (www.defense.gov)

- ^ announced (www.ft.com)

- ^ pledged additional support (www.ft.com)

- ^ freeze around US$20 billion in debt (www.reuters.com)

- ^ Germany (www.bundesfinanzministerium.de)

- ^ cities across Ukraine (www.politico.com)

- ^ infrastructure (www.gov.uk)

- ^ Sergey Kozlov / EPA-EFE (webgate.epa.eu)

- ^ defaulted on loans (www.outlookindia.com)

- ^ sting but do not cripple (www.politico.eu)

- ^ data on key economic indicators (www.bloomberg.com)

- ^ recent report (papers.ssrn.com)