Inflation will probably melt away in 2022 – central banks will do far more harm trying to tackle it

- Written by Brigitte Granville, Professor of International Economics and Economic Policy, Queen Mary University of London

It remains to be seen whether the omicron variant will shift Sars-CoV-2 towards becoming manageably endemic. But as and when this happens, there will still be “long COVID” to contend with. The latest headlines about inflation – a 7% annual rise[1] in the US and more tough talk[2] from Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell about bringing it down – confirm that something similar is happening with the global economy: it will be shaped by the after-effects of the pandemic even when all restrictions have been lifted.

To understand how this overhang effect may play out in 2022 requires looking back at how the pandemic has affected growth and inflation. The key lies in decisions taken after the initial phase in 2020 when governments shut down large parts of their economies while compensating households and businesses for lost income to prevent an economic depression. People both saved more than usual and redirected their spending from services like eating out or travel to goods for the home – notably digital equipment for remote working and leisure.

Such goods started running out of stock and it took longer than usual for supplies to recover, not least because COVID restrictions had hit the global supply chain[3]. The same went for other key consumer requirements such as energy: as demand for oil rebounded, the supply was constrained[4] either by political decisions, such as the Opec+ cartel declining to raise production, or the financial fragility of US shale oil producers.

Shortages have caused inflationary pressure, which has also been aggravated by factors linked to the climate emergency. Since replacing coal with a “greener” fossil fuel in electricity generation is one of the quickest ways to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, there has been increased demand for natural gas. And in food markets, agricultural production has been damaged by the growing frequency of extreme weather events.

Misapprehensions about inflation

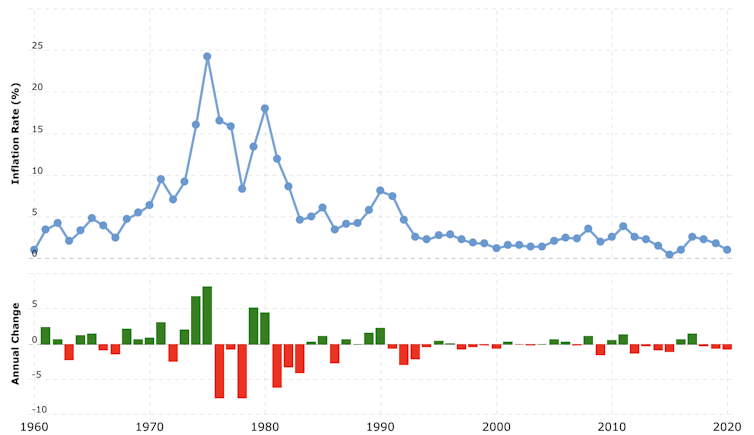

In many advanced industrial countries, headline inflation rose by the end of 2021 to its highest level in two decades: that annual rate of 7%[5] in the US in December, and 5% in the eurozone[6] (the two regions measure inflation in slightly different ways).

Meanwhile, the bounce in world economic growth in 2021 after the initial pandemic slump has been naturally giving way to a slower pace of growth. This is in line with more normal trends now that major economies have returned to[7], or are approaching, their pre-pandemic levels of output. This combination of slowing growth and rising prices – often labelled “stagflation” – is pernicious if it continues, attracting widely voiced concerns as 2021 wore on.

I would argue, however, that this threat is exaggerated. It stems to a considerable extent from a confusion between an increase in price levels and genuine inflation defined as persistent and volatile increases in the rate of price growth. This is a subject close to my heart, which I discuss in my 2013 book Remembering Inflation[8].

The price rises can be largely explained by this problem of suppliers being unable to provide enough goods to meet the rebound in consumer demand. And one key development which became apparent by the end of 2021 was that the supply of manufactured goods had recovered sufficiently to correct this inflationary imbalance.

UK inflation, 1960-present