you're probably worse at it than you realise

- Written by Adrian R. Camilleri, Senior Lecturer in Marketing, University of Technology Sydney

Ever relied on an online review to make a purchasing decision? How do you know it was actually genuine?

Consumer reviews can be hugely influential, so it’s hardly surprising there’s a thriving trade in fake ones. Estimates of their prevalence vary – from 16% of all reviews on Yelp[1], to 33% of all TripAdvisor[2] reviews, to more than half in certain categories[3] on Amazon.

So how good are you at spotting fake consumer reviews?

I surveyed 1,400 Australians about their trust in online reviews and their confidence in telling genuine from fake. The results suggest many of us may be fooling ourselves about not being fooled by others.

In strangers we trust

Online consumer reviews were the equal-second most important source for information about products and services, after store browsing. Most of us rate consumer reviews – the views of perfect strangers – just as highly as the opinion of friends and family.

Trust is central to the importance of reviews in our decision-making. The following chart shows the trust results broken down by age: in general, people most trust product information from government sources and experts, followed by consumer reviews.

The chart below displays trust ratings according to website, with the most trusted sources for reviews being TripAdvisor.com.au[4], Google Reviews[5] and ProductReview.com.au[6].

Those aged 23-38 tended to trust sites the most, and those above 55 tended to trust sites the least.

While 73% of participants said they trusted online reviews at least a moderate amount, 65% also said it was likely they had read a fake review in the past year.

The paradox of these percentages suggests confidence in spotting fake reviews. Indeed, 48% of respondents believed they were at least moderately good at spotting fake reviews. Confidence tended to correlate with age: those who were younger tended to rate themselves as better at detecting fake reviews.

In my opinion, respondents’ confidence is a classic example of overconfidence[7]. It’s a well-documented paradox of human self-perception, known as the Dunning-Kruger effect[8]. The worse you are at something, the less likely you have the competence to know how bad you are.

The fact is most humans are not particularly good at distinguishing between truth and lies.

A 2006 study involving almost 25,000 participants found that lie-truth judgments averaged just 54% accuracy[9] – barely better than flipping a coin. In a study looking more specifically at online reviews (but with only a small number of judges), Cornell University researchers[10] found an accuracy rate of about 57%. A similiar study based at the University of Copenhagen found an accuracy rate of about 65%[11], with information about reviewers improving scores slightly.

What we look for

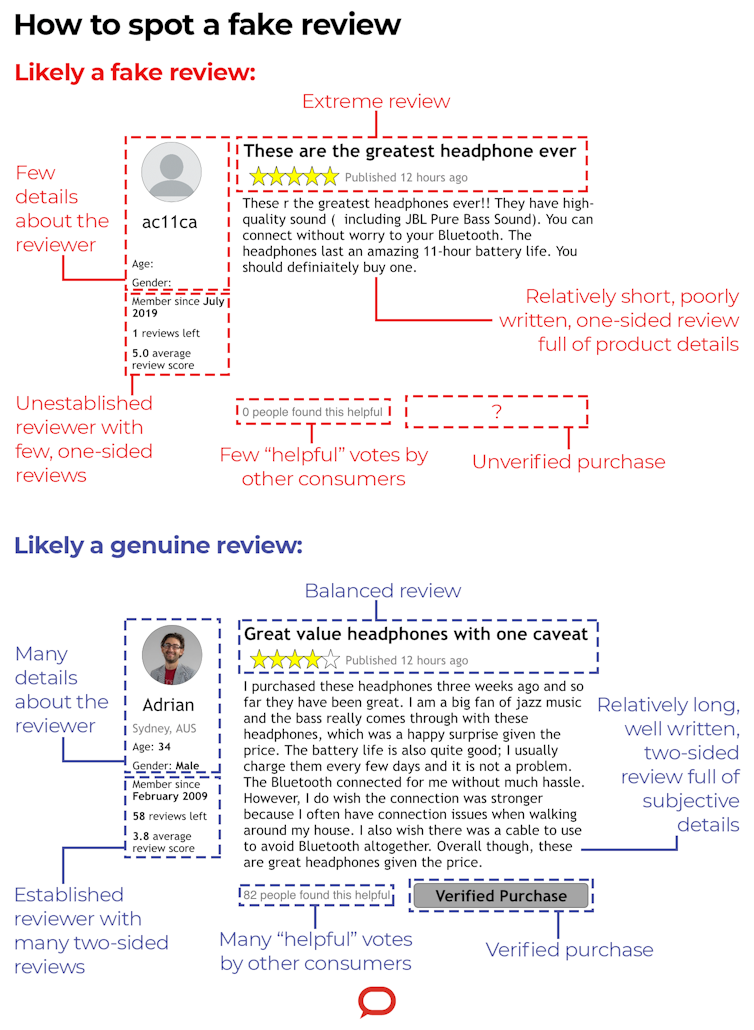

So what tends to sway people’s judgement about whether a review is fake or not? My research suggests the most important attribute people look out for is “extremity” – going over the top in one-sided praise or criticism.

This sentiment is a relatively sound rule of thumb, supported by analysis[12]. Studies suggest fake reviews also tend to:

- focus on describing product attributes and features

- have much fewer subjective and anecdotal details

- be shorter than others

- be relatively more difficult to read (probably due to fake reviewers being hired from foreign countries).

Fake reviews might also be identified by characteristics of the reviewer[13]. Their profiles tend to be new and unverified[14] accounts with few details and little or no history of other reviews. They will have gained very few “helpful” votes from others.

The Conversation/Author provided content, CC BY-ND[15]

Test yourself

With all this in mind, it’s now’s time to see how good you are at spotting fake reviews with this quiz.

Chances are you didn’t do as well as you thought you would. That’s because clever fraudsters work to hide all the attributes of fake reviews outlined above.

So two final pieces of advice.

Use some technology to help. Two websites I recommend are Fakespot.com[16] and ReviewMeta.com[17]. In my experience, both do a good job weeding out suspicious reviews (tip: be sure to delete domain suffixes such as “.au” from the URLs you check).

Also check out multiple review sites to get second, third and fourth opinions. It is less likely a fraudster will be paying for fake reviews on every platform.

The Conversation/Author provided content, CC BY-ND[15]

Test yourself

With all this in mind, it’s now’s time to see how good you are at spotting fake reviews with this quiz.

Chances are you didn’t do as well as you thought you would. That’s because clever fraudsters work to hide all the attributes of fake reviews outlined above.

So two final pieces of advice.

Use some technology to help. Two websites I recommend are Fakespot.com[16] and ReviewMeta.com[17]. In my experience, both do a good job weeding out suspicious reviews (tip: be sure to delete domain suffixes such as “.au” from the URLs you check).

Also check out multiple review sites to get second, third and fourth opinions. It is less likely a fraudster will be paying for fake reviews on every platform.

References

- ^ 16% of all reviews on Yelp (doi.org)

- ^ 33% of all TripAdvisor (www.news.com.au)

- ^ more than half in certain categories (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ TripAdvisor.com.au (www.tripadvisor.com.au)

- ^ Google Reviews (support.google.com)

- ^ ProductReview.com.au (www.productreview.com.au)

- ^ overconfidence (theconversation.com)

- ^ Dunning-Kruger effect (psycnet.apa.org)

- ^ lie-truth judgments averaged just 54% accuracy (doi.org)

- ^ Cornell University researchers (myleott.com)

- ^ of about 65% (aclweb.org)

- ^ analysis (doi.org)

- ^ characteristics of the reviewer (doi.org)

- ^ unverified (doi.org)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ Fakespot.com (www.fakespot.com)

- ^ ReviewMeta.com (reviewmeta.com)

Authors: Adrian R. Camilleri, Senior Lecturer in Marketing, University of Technology Sydney