Frydenberg’s budget looks toward zero net debt, but should this be our aim?

- Written by Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW

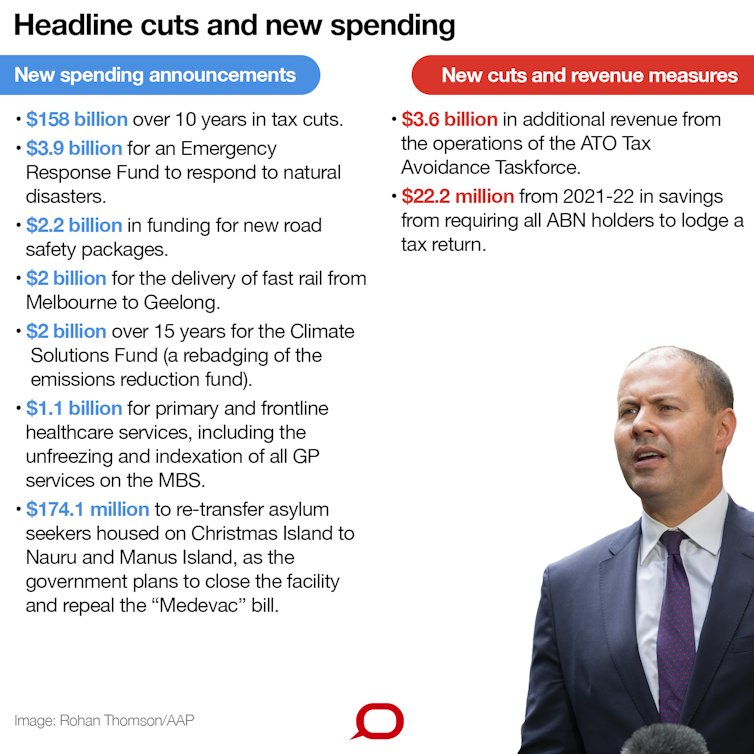

In his budget speech tonight Treasurer Josh Frydenberg announced that under a Coalition government we will see a decade of surpluses that will “continue to build toward 1% of GDP within a decade”.

He went on: “we climb the mountain and reach our goal of eliminating Commonwealth net debt by 2030 or sooner.”

But a funny thing happened on the way to paying off the debt.

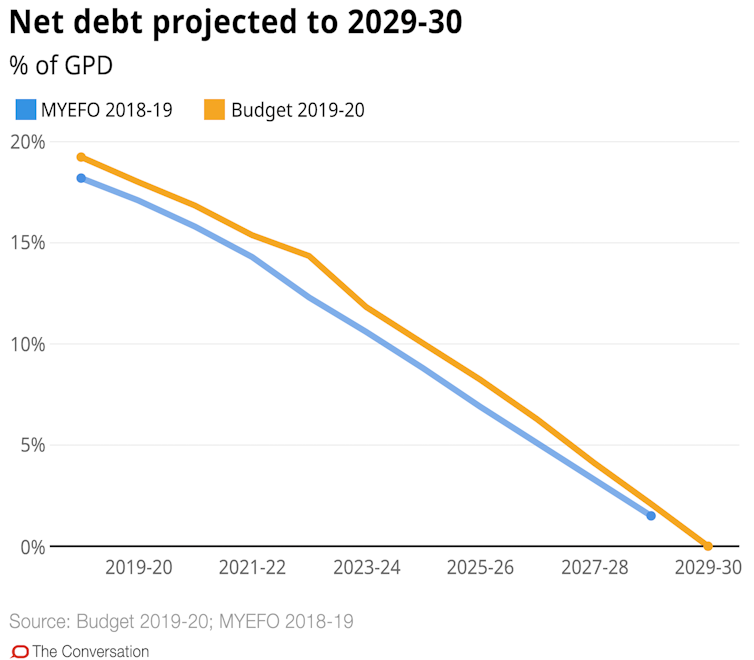

As the budget papers point out, net debt as a proportion of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is predicted in the budget to peak at 19.2%.

You might ask, then, how do we get from 19% to 0% debt/GDP in ten years if we’re generating a surplus of 1% per annum?

A small part of the answer is that with the economy forecast to grow at 3% a year, GDP is a fair bit bigger 10 years from now. And a 1% surplus of a bigger GDP number is a bigger dollar surplus. This has a larger impact on net debt.

That’s part of the story, but not much of it. If we make the most generous assumptions in favour of the treasurer and his surpluses (even if you believe them), they’re only paying down about two-thirds of the debt.

The case of the vanishing debt

So how does the treasurer get the rest of the debt to disappear?

The budget documents, voluminous though they are, don’t have the answers. But there are only a handful of logical possibilities.

First, let’s unpack what net debt is. Net debt is basically the gross debt issued by the government (for example, by issuing government bonds) minus the assets the government holds.

The surpluses Frydenberg announced help reduce gross debt. So, the debt-disappearing act has to involve some assets getting bigger.

The leading possibility concerns the Future Fund (Australia’s sovereign wealth fund). Simply put, if the Future Fund earns, say, 8% per annum, then those assets are going to be growing a lot faster than GDP. This reduces debt to GDP quite apart from anything else.

Another way to think about it is that the Australian government is running a big hedge fund with a lucrative profit opportunity. If it can earn 8% per annum while the government is funding this with debt that costs less than 2% (as is the case currently, given yields on 10-year Australian government bonds), then that’s a great deal.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m fine with that. But to the extent that debt reduction is coming from the Future Fund, it has nothing to do with fiscal rectitude.

Read more:

Iron ore dollars repurposed to keep the economy afloat in Budget 2019[1]

An even more obscure possibility is that asset values are being hypothetically affected by assumptions about the interest rate the government will pay on its debt. Currently, it is about 1.72%, but the budget documents suggest a return to long-run historical levels of around 5

First, that seems very unlikely to happen in a post-GFC world. Second, it’s unclear that it’s of a sufficient magnitude to explain away the vanishing debt. And third, it’s an accounting artefact, not a matter of economic substance. Again, whatever it is, it’s not fiscal rectitude.

The only other possibilities are even more remote. A massive increase in the value of the essentially defective National Broadband Network? A colossal spike in student loan repayments while future students pay their own way? Nope and nope.

Should we be aiming for zero net debt?

Another question altogether is whether it is wise to reduce government debt to zero in the coming decade.

Fiscal discipline is good and avoiding structural budget deficits is important.

But as I’ve written before, we live in an age of “secular stagnation”, where there is a glut of global savings chasing too few productive investment opportunities and where economic growth is permanently lower than in previous decades.

As former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers has pointed out, in a secular-stagnation world it will likely take a lot more government spending to sustain full employment and reasonable wages growth without financial bubbles.

Or, to put it another way, if the Australian government can borrow at less than 2%, there are a lot of attractive public investments in physical and social infrastructure that should be made. The idea of “Social Return Accounting”, which the UNSW Grand Challenge on Inequality launched last year and I wrote about here, offers a framework for thinking about this.

The live hand of Peter Costello

The treasurer presumably didn’t mean to be ironic when he said of the down-to-zero debt paydown:

Only one side of politics can do this… John Howard and Peter Costello paid off Labor’s debt.

But it is ironic that Peter Costello’s Future Fund is doing a good deal of the heavy lifting in paying off Josh Frydenberg’s debt.

A small part of the answer is that with the economy forecast to grow at 3% a year, GDP is a fair bit bigger 10 years from now. And a 1% surplus of a bigger GDP number is a bigger dollar surplus. This has a larger impact on net debt.

That’s part of the story, but not much of it. If we make the most generous assumptions in favour of the treasurer and his surpluses (even if you believe them), they’re only paying down about two-thirds of the debt.

The case of the vanishing debt

So how does the treasurer get the rest of the debt to disappear?

The budget documents, voluminous though they are, don’t have the answers. But there are only a handful of logical possibilities.

First, let’s unpack what net debt is. Net debt is basically the gross debt issued by the government (for example, by issuing government bonds) minus the assets the government holds.

The surpluses Frydenberg announced help reduce gross debt. So, the debt-disappearing act has to involve some assets getting bigger.

The leading possibility concerns the Future Fund (Australia’s sovereign wealth fund). Simply put, if the Future Fund earns, say, 8% per annum, then those assets are going to be growing a lot faster than GDP. This reduces debt to GDP quite apart from anything else.

Another way to think about it is that the Australian government is running a big hedge fund with a lucrative profit opportunity. If it can earn 8% per annum while the government is funding this with debt that costs less than 2% (as is the case currently, given yields on 10-year Australian government bonds), then that’s a great deal.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m fine with that. But to the extent that debt reduction is coming from the Future Fund, it has nothing to do with fiscal rectitude.

Read more:

Iron ore dollars repurposed to keep the economy afloat in Budget 2019[1]

An even more obscure possibility is that asset values are being hypothetically affected by assumptions about the interest rate the government will pay on its debt. Currently, it is about 1.72%, but the budget documents suggest a return to long-run historical levels of around 5

First, that seems very unlikely to happen in a post-GFC world. Second, it’s unclear that it’s of a sufficient magnitude to explain away the vanishing debt. And third, it’s an accounting artefact, not a matter of economic substance. Again, whatever it is, it’s not fiscal rectitude.

The only other possibilities are even more remote. A massive increase in the value of the essentially defective National Broadband Network? A colossal spike in student loan repayments while future students pay their own way? Nope and nope.

Should we be aiming for zero net debt?

Another question altogether is whether it is wise to reduce government debt to zero in the coming decade.

Fiscal discipline is good and avoiding structural budget deficits is important.

But as I’ve written before, we live in an age of “secular stagnation”, where there is a glut of global savings chasing too few productive investment opportunities and where economic growth is permanently lower than in previous decades.

As former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers has pointed out, in a secular-stagnation world it will likely take a lot more government spending to sustain full employment and reasonable wages growth without financial bubbles.

Or, to put it another way, if the Australian government can borrow at less than 2%, there are a lot of attractive public investments in physical and social infrastructure that should be made. The idea of “Social Return Accounting”, which the UNSW Grand Challenge on Inequality launched last year and I wrote about here, offers a framework for thinking about this.

The live hand of Peter Costello

The treasurer presumably didn’t mean to be ironic when he said of the down-to-zero debt paydown:

Only one side of politics can do this… John Howard and Peter Costello paid off Labor’s debt.

But it is ironic that Peter Costello’s Future Fund is doing a good deal of the heavy lifting in paying off Josh Frydenberg’s debt.

References

- ^ Iron ore dollars repurposed to keep the economy afloat in Budget 2019 (theconversation.com)

Authors: Richard Holden, Professor of Economics, UNSW