Protectionism has a long history in the US – so its return should not be all that surprising

- Written by Steve Schifferes, Honorary Research Fellow, City Political Economy Research Centre, City St George's, University of London

While Britain has for the most part had a strong commitment to free trade[1], it’s a very different story in the US, which has a long history of protectionism. This means that President Donald Trump’s tariff wars[2] are playing out very differently politically on his side of the Atlantic. And there is no certainty that domestic opposition will be strong enough to curb his enthusiasm for using tariffs as a weapon.

Britain’s political economy is still shaped by the battle over free trade that took place nearly 200 years ago. The bitter debate over the Corn Laws[3], which put high tariffs on imported food to protect UK landowners, led to a political triumph for the new Liberal party. It also led to wide support[4] among working people and manufacturers for a policy of free trade.

Britain’s domination[5] of the world economy in the 19th century owed much to the triumph of free trade. And the British public[6] still largely backs free trade today.

In contrast, many American politicians in the 19th century believed that US industry needed protection from its more efficient rivals. It was Alexander Hamilton[7], one of the authors of the US constitution and America’s first treasury secretary, who introduced tariffs in 1789[8]. Hamilton cited the need to protect America’s “infant industries”[9] from foreign competition.

By the end of the 19th century, US manufacturers had surpassed[10] their British rivals. Protectionism, however, remained a cornerstone of American international economic policy. It was the expanding US domestic market and not exports to foreign countries that was driving the growth of America’s giant corporations – which were closely allied with the ruling Republican party[11].

Between 1861 and 1933, US tariffs on foreign imports averaged 50%[12] – among the highest in the world. Tariffs also contributed nearly half[13] of all government revenues. Federal income taxes were only introduced, after much opposition, in 1913[14].

The postwar turn

It was at the end of the second world war that the US moved to embrace free trade[15]. But even then, political support was weak. In 1948 the US Congress rejected the proposed International Trade Organization[16], which would have regulated international trade. This had been part of the Bretton Woods[17] negotiations that set up the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, and gave the dollar the leading role in the global economy.

The determining factor in the US endorsement of free trade was not economic gain, but political necessity. With the cold war in full swing, the US understood the need to help Europe and Japan’s economies flourish in order to resist the appeal of communism.

With American industry – greatly expanded by war – dominating the world economy[18], the political cost of allowing more foreign imports was low. And the potential benefits of selling more American goods abroad looked promising.

But this began to change in the 1970s, driven by the success of Japanese car manufacturers. In 1981 the US negotiated with Japan’s carmakers a voluntary cap on exports[19] to the US of 1.68 million cars per year.

The WTO and after

Nevertheless, the US was still the driving force in trade liberalisation. Both Republicans and Democrats endorsed the benefits of globalisation, urging the spread of free trade and economic deregulation globally.

It was only in 1995, under President Bill Clinton, that the World Trade Organization[20] (WTO) was created, giving full legal status to trade negotiations for the first time. But Clinton’s plan to host talks in Seattle in 1999 had to be cancelled after demonstrations[21] by trade unionists and environmentalists paralysed the city.

The next meeting was held in 2001 in Doha, Qatar[22] – where no protests were allowed – to launch talks that would widen trade liberalisation to cover agriculture and services. The most important result however was that China was admitted to the WTO[23], giving it full access to US and European markets.

It soon became clear that China’s manufacturing sector had a huge advantage over its US rivals. China’s trade surplus[24] with the US soared (meaning it sold more to America than it bought from it), while US manufacturing jobs in the “rust belt” industrial regions fell into decline.

While economists could argue[25] that overall, the benefits to US consumers of cheaper goods outweighed the costs to workers in some industries, this came at a a high political cost[26].

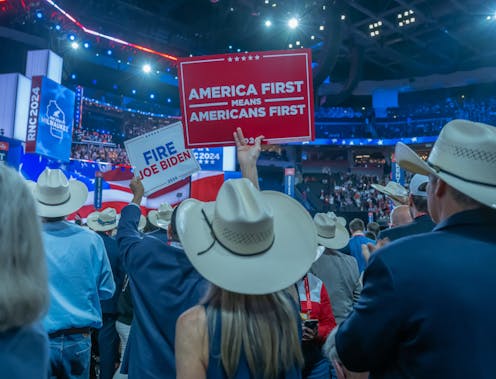

It was Trump who saw the opportunity this gave the Republican party to champion the white working class. These voters often felt deserted[28] by the Democrats. Trump’s support of high tariffs, with the aim of restoring US manufacturing dominance and “reshoring”[29] industry, may be unlikely to succeed in that aim. But that does not mean it is unpopular in those heartlands – the key swing states[30] that Trump won in the 2024 election.

Attempts by the Biden administration[31] to move in the same direction, including keeping Trump-era tariffs on Chinese imports and introducing subsidies for key manufacturing sectors, shows the way[32] the political wind is blowing.

Of course, if the tariff wars cause a major recession in the US, this would be politically damaging. But the US is far less dependent[33] on international trade than rivals like Japan, China and the EU.

Americans are doubtful[34] about the value of expanding free trade. The issue is not high on the list of issues that most worry US voters, although there are sharp partisan divides[35] on whether Trump’s higher tariffs will benefit or harm the US economy.

The Democrats are likely to fight the next election on domestic economic issues such as defending social security and boosting jobs and income. Meanwhile the WTO has effectively been rendered impotent[36], and we are unlikely to return to a world of globally agreed trade rules.

In fact, Britain, with one of the most open economies[37] in the world, is particularly vulnerable. So, for the US, the political and economic cost of a trade war would be disproportionately felt overseas – something that the president will be well aware of.

References

- ^ free trade (www.parliament.uk)

- ^ tariff wars (theconversation.com)

- ^ Corn Laws (www.historyextra.com)

- ^ wide support (global.oup.com)

- ^ domination (www.bbc.co.uk)

- ^ British public (www.gov.uk)

- ^ Alexander Hamilton (home.treasury.gov)

- ^ 1789 (www.usitc.gov)

- ^ “infant industries” (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ surpassed (academic.oup.com)

- ^ ruling Republican party (global.oup.com)

- ^ averaged 50% (www.nber.org)

- ^ nearly half (www.usitc.gov)

- ^ in 1913 (www.archives.gov)

- ^ free trade (www.investopedia.com)

- ^ International Trade Organization (academic.oup.com)

- ^ Bretton Woods (theconversation.com)

- ^ dominating the world economy (www.history.com)

- ^ voluntary cap on exports (americancompass.org)

- ^ World Trade Organization (www.wto.org)

- ^ demonstrations (www.seattle.gov)

- ^ Doha, Qatar (www.wto.org)

- ^ China was admitted to the WTO (theconversation.com)

- ^ China’s trade surplus (www.epi.org)

- ^ economists could argue (blogs.sussex.ac.uk)

- ^ a high political cost (www.hup.harvard.edu)

- ^ Jenson/Shutterstock (www.shutterstock.com)

- ^ often felt deserted (www.theatlantic.com)

- ^ “reshoring” (www.investopedia.com)

- ^ key swing states (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ Biden administration (theconversation.com)

- ^ shows the way (blogs.sussex.ac.uk)

- ^ far less dependent (theconversation.com)

- ^ doubtful (www.pewresearch.org)

- ^ sharp partisan divides (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ rendered impotent (www.foreignaffairs.com)

- ^ most open economies (niesr.ac.uk)