For the next prime minister to solve the UK’s productivity problem, they must attract more foreign investment – here’s how

- Written by Costas Milas, Professor of Finance, University of Liverpool

The British economy has a serious productivity problem that will have to be addressed by the next government. According to data from[1] the OECD (the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), productivity measured as GDP per hour worked in the UK only rose 4% between 2015 and 2022. The average increase across all 43 OECD countries over the same period was 7%.

The UK is also in the bottom 30% for productivity among all OECD economies and shows no signs of improving. The latest statistics[2] from the UK’s Office for National Statistics (ONS) suggest that in the first quarter of 2024, GDP per hour worked was only up 0.1% year on year, compared to a historic average[3] of 1.8%. Meanwhile, GDP per worker, the other common measure of labour productivity, was up just 0.8% over the same period, compared to a historic average[4] of 1.4%.

Extremely weak productivity leaves little room for wage increases above the rate of inflation. This hampers the government’s tax revenues, contributing to[5] a persistent gap between spending and income: the budget deficit is currently 4.6% of GDP[6] according to the International Monetary Fund.

Indeed, the next government is potentially facing[7] a £33 billion “hole” in the public finances. This will put upward pressure on borrowing costs, so improving productivity is vital.

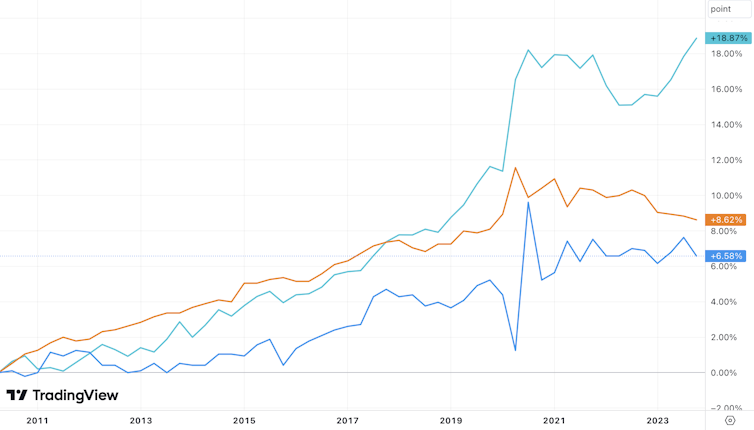

The productivity gap (% increase since 2010)

This is not a new problem for the UK; economists have been talking about it for years. It is closely related to business investment, which the National Institute of Economic and Social Research says has declined[9] from close to 14% of GDP in the 1960s and 1970s to 9% since 2008.

Professor David Miles, a member of the Budget Responsibility Committee at the government’s Office for Budget Responsibility and an ex-member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee, has cited deindustrialisation[10]. He noted that 30 to 40 years ago, the UK was a bigger manufacturer[11] and less of a services provider, and that productivity growth tends to be stronger in manufacturing.

So how does the UK improve productivity? One way is to attract more foreign investment, which is disproportionately important to the UK economy. According to a 2021 report[12] from the UK Department for International Trade, just 4% of local business premises are foreign owned, but they account for[13] nearly 40% of the nation’s turnover.

Firms set up by foreign companies account for between 12% and 21%[14] of local employment depending on the region, with London highest and south-west England lowest. Yet they tend to be around 50%[15] more productive than other UK firms, investing up to five times[16] more on R&D (research and development). Most likely, these firms have to be more productive to overcome the sunk costs of entering a new market and competing with domestic incumbents.

Greater productivity means that their wages are 5% higher[17] than UK-owned firms. They are also better managed, and more likely to collaborate with other organisations and share knowledge. On average, it takes[18] about four years for this knowledge to “spill over” to domestic firms. For every ten percentage-point increase in foreign presence in a UK industry, it raises the productivity of that industry by 0.5%.

How to improve foreign investment

So what drives foreign investment? This is the subject of recent research[19], which is yet to be peer reviewed, that two colleagues from the University of Macedonia in Greece, Theodore Panagiotidis and George Papapanagiotou, and I conducted.

Our main findings are as follows:

1. Economic uncertainty

Foreign investment falls when companies are more uncertain about UK economic policy. As a gauge, we used an index[20] on economic policy uncertainty, which measures references to it in the media.

In recent years, for instance, uncertainty has been created by the 2016 Brexit vote[21], the unfunded tax cuts[22] announced by Prime Minister Liz Truss in 2022, and more generally the fact that there have been six different[23] chancellors of the exchequer in the past eight years.

The chart below shows how foreign investment was affected by the Brexit vote. It shows that investment became more volatile after David Cameron announced[24] the EU referendum in 2013, then all the more so after the vote three years later.

Foreign inflows as a % of GDP