The idea that US interest rates will stay higher for longer is probably wrong

- Written by Alan Shipman, Senior Lecturer in Economics, The Open University

The 0.4% rise[1] in US consumer prices in March didn’t look like headline news. It was the same as the February increase, and the year-on-year rise of 3.5%[2] is still sharply down from 5% a year ago.

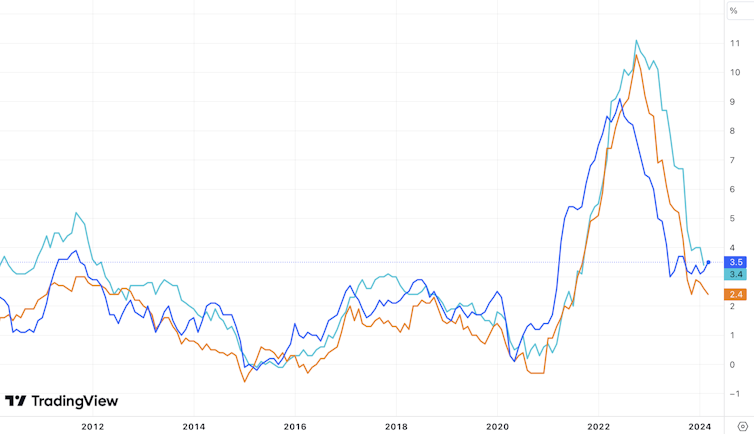

All the same, this modest uptick in annual inflation from 3.2% in February has cast doubt[3] on whether the US central bank, the Federal Reserve, can afford to cut headline interest rates as fast as it has been signalling[4]. To further complicate matters, a gap has opened up between the US inflation rate and that of other regions, notably the EU.

US inflation vs EU and UK

Financial markets’ instant reaction was bearish. They dumped stocks while buying EU government bonds, in expectation of a boost from the European Central Bank cutting its rates sooner. They also bought the US dollar, anticipating it will strengthen when European rates come down. But how is this likely to play out?

Can they all be right?

The US economy has returned to steady expansion[6] after the COVID-19 pandemic disruption of 2020-22, while Europe is struggling to achieve any growth[7]. This helps to explain the difference in the inflation figures.

The strength of the US economy was already putting pressure on the Fed to cut less quickly. A higher interest rate helps to stop strong demand straining supply chains and making prices rise too fast. The quickening of consumer-price inflation gives the Fed an added incentive to be hawkish on rates – to convince businesses and households that it will keep monetary conditions tight until inflation falls back to the 2% target.

The interest rates[8] on advance purchases of US debt (the “Fed futures” market) show that a majority of traders now expect the Fed will not drop its interest rate from the current level (of 5.25% to 5.5%) to below 5% until December. A week ago, most thought this would have happened by September.

The trouble is that an extended period of higher rates could be very damaging because there’s so much debt[9] in the system. In particular, last year’s wobbles in the US banking sector[10], and wider concerns[11] about institutional investors exposed to a slump in commercial real estate, are strong incentives to reduce credit costs before too long.

Consequently, few believe[12] the US headline interest rate will still be at present levels a year from now. Yet the longer that inflation endures, the more the pressure to delay further rate cuts. Most Americans[13] now believe inflation will stay around 3% for the next year, an expectation echoed in markets for assets viewed as protecting against inflation (such as gold and cryptocurrencies).

Election-year inflation dangers

An especially fraught presidential election race also limits the Fed’s manoeuvring room. The White House has pitched[14] its 2024-25 federal budget as helping to subdue inflation, by lowering working families’ living costs and forcing companies to pass-on cost savings.

But while Joe Biden aims to spend US$7.3 trillion (£5.8 trillion) in pursuit of his plans, congressional opponents are likely to block[15] many of the tax increases intended to pay for them.

That’s likely to mean a continued widening of the US federal deficit, injecting more demand and keeping up inflationary pressure. That pressure could be worsened by the punitive tariffs that Republicans want[16] to impose on cheap imports, to which many Democrats are sympathetic. An increasingly bipartisan push for tighter border controls would also raise US inflation risk, by stemming the inflow of cheap labour that has kept unskilled wages down.

US federal deficit