experts react to UK government's plan to get the economy moving

- Written by Phil Tomlinson, Professor of Industrial Strategy, Co-Director Centre for Governance, Regulation and Industrial Strategy (CGR&IS), University of Bath

Jeremy Hunt’s 2023 spring budget[1] covers employment, energy, enterprise and much more besides. The plan has already been dubbed his “back to work budget[2]”, although he has called it a “budget for growth[3]”.

Hunt was appointed chancellor in a bid to calm financial markets after last year’s dramatic mini-budget[4] under previous prime minister Liz Truss. His ongoing efforts to maintain this mood have included giving away several major chunks of this announcement beforehand. Now that Hunt has provided more of the detail, here’s what our panel of academic experts think of the government’s plans for the economy:

Evidence for ‘levelling up’ measures is mixed

Phil Tomlinson, Professor of Industrial Strategy, School of Management, University of Bath

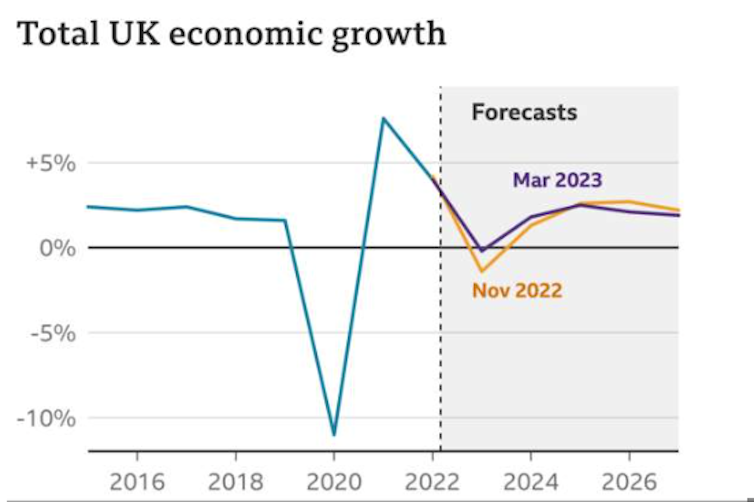

The short-term outlook for the UK economy is better than expected[5]. Economic growth picked up in January[6], falling gas prices have reduced the cost of the government’s energy support package, and public borrowing is likely to be £30 billion lower[7] than last November’s Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecast. This has allowed the chancellor some leeway to deal with some of the economy’s long-standing challenges.

Since the 2008 global financial crisis, the UK economy has been largely stagnant[8]. It remains the only country in the G7 not to have recovered to its pre-pandemic level of national income[9]. Business investment has been weak for decades[10] (and especially so, since the 2016 Brexit referendum), while the labour market has lost almost a million workers[11] since 2019. And then there is the “levelling up[12]” needed to reduce the UK’s wide regional inequalities.

Today’s budget seeks to address some of these issues. The childcare support package is geared towards helping young parents return to the labour market. And while benefiting higher earners, changes to the lifetime tax-free pension allowance and the annual cap on contributions are intended to encourage older and highly skilled professionals – especially NHS doctors – to remain in their posts, rather than take early retirement.

The chancellor also announced 12 new investment zones[13] in the combined authority regions of the north of England and Midlands, and in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Each will receive £80 million of funding for upgrading skills, specialist business support, local infrastructure and for tax incentives. The goal is to attract new business investment and build innovation clusters in key sectors (such as advanced manufacturing and life sciences) to generate dynamic growth in “left behind” regions.

The funding itself, however, is not overly generous, while the evidence on similar initiatives[14] (including freeports and enterprise zones) is mixed. For instance, there are concerns such zones merely shift business activity from places located outside a zone to places located inside a zone (rather than attracting new investment). Many “left behind” towns and cities not in a combined authority region will also miss out on this initiative.

Too little, too late for business?

Steven McCabe, Associate Professor, Birmingham City Business School

Will businesses[15], which have suffered so much in recent years, welcome chancellor Jeremy Hunt’s spring statement?

Many will claim what’s offered is too little, too late. Indeed, a lot of businesses are merely surviving because of spiralling energy costs[16] and increased wages.

Hunt, who owes his political renaissance to the disastrous consequences of his predecessor Kwasi Kwarteng’s[17] “mini-budget[18]” in 2022, attempts to continue the return to stability with optimism of better times ahead.

He will continue with the intention, which Rishi Sunak set out when he was chancellor, of raising corporation tax[19] from 19% to 25%. This will help to repair damage to public finances caused by the pandemic and made worse by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – as well as Liz Truss[20]’s ill-considered dash for growth. This announcement will be greeted with mixed emotions by businesses.

Changes to pension pots[21] and contributions may help to retain and attract high earners. Hunt also hopes to encourage a significant number of the nine million “economically inactive[22]” (people who are neither working nor looking for work) into employment.

Undoubtedly the most eye-catching announcement made by the chancellor is funding for 12 investment zones[23] to “supercharge” high-tech growth across the UK.

Cynics may stress that Hunt’s assertion of the importance of investing in growth and opportunity comes from a government that’s been in power for 13 years[24]. Indeed, the fact remains that the UK is the only G7 country[25] with a smaller economy than before COVID. And political inability, striking workers and a disappearing public health system certainly haven’t helped.

Not not a recession

Alan Shipman, Senior Lecturer in Economics, Open University

The chancellor has announced that the economy will avoid a “technical recession[26]” this year. This is because that requires two-quarters of falling GDP, whereas the OBR, which provides independent economic forecasts and analysis of the public finances, now shows falls in just one-quarter.

But most people would probably still view a 0.2% drop[27] in the size of the economy across the year as a recession.

Hunt has responded to post-Brexit labour shortages with measures to push more of the eight million[28] inactive working-age people[29] into paid employment. That includes the half million sidelined by health problems[30] since the pandemic.

The need for more workers to revive output reflects the stagnation of UK labour productivity since 2008[31], which has prevented real wage growth in the UK and left it unusually vulnerable to last year’s jump in living costs.