experts react to the new UK government's spending and tax-cut plans

- Written by Phil Tomlinson, Professor of Industrial Strategy, Deputy Director Centre for Governance, Regulation and Industrial Strategy (CGR&IS), University of Bath

UK chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng has just launched the biggest package of tax cuts[1] in half a century. This will involve around £45bn of reductions for people and businesses by 2027 – 50% more than anticipated[2] before the mini-budget announcement.

Amid the worst cost of living crisis[3] in a generation, Liz Truss’s government wants to boost growth and usher in “a new era” for Britain. It is targeting a 2.5% annual growth rate via a three-pronged approach of reforming the supply side of the economy, taking a “responsible approach” to public finances and cutting taxes.

The tax cut element was trailed heavily during the recent Tory leadership contest, but now that we have some firm details, our expert panel offers their views on Kwarteng’s plan[4].

Gambling on growth

Phil Tomlinson, Professor of Industrial Strategy, Deputy Director Centre for Governance, Regulation and Industrial Strategy, University of Bath

The UK economy is stagnant. Prices continue to rise, while consumer[5] and business[6] confidence plummets. In response, the UK chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng has presented a mini-budget which he says will “go for growth”.

The headline tax and stamp duty cuts, alongside recent energy price caps, are aimed at easing household and business finances. Then there are plans for regional investment zones[7] designed to offer tax incentives and fewer regulations.

All of this is being funded by huge levels of public borrowing[8] in the hope of boosting consumer spending, stimulating enterprise and staving off recession. The government is gambling on economic growth to pay off its enormous debts.

And it’s quite a gamble. The stamp duty cut for example, will only fuel an already inflated housing market. And “enterprise zones” do not guarantee[9] new investment.

In fact, this mini budget is worryingly reminiscent of another Conservative gamble from 50 years ago. In 1972, the then chancellor Anthony Barber[10], announced massive tax cuts and higher public borrowing in a “dash for growth” at a time of high inflation and rising unemployment.

The “Barber boom” is now a textbook case of how not to engage in fiscal largesse. It led to a temporary uplift in growth, and then a debilitating hangover of even higher inflation, a sterling crisis and Britain eventually having to go cap in hand[11] to the International Monetary Fund.

Today, the markets are already nervous. A hard Brexit has exacerbated the UK’s record trade deficit[12], with the value of sterling recently dropping[13] to its lowest level against the US dollar since 1985. This raises import inflation, and the Bank of England has begun to respond aggressively by raising interest rates[14], hitting borrowers and business investment, and raising the costs of servicing government debt.

There remains a strong case for a fiscal policy targeted at promoting new business investment, infrastructure, skills and public services. Unfortunately, this “trickle down”[15] mini-budget is unlikely to deliver that elusive long-term growth.

Personal finance

Jonquil Lowe, Senior Lecturer in Economics and Personal Finance, The Open University

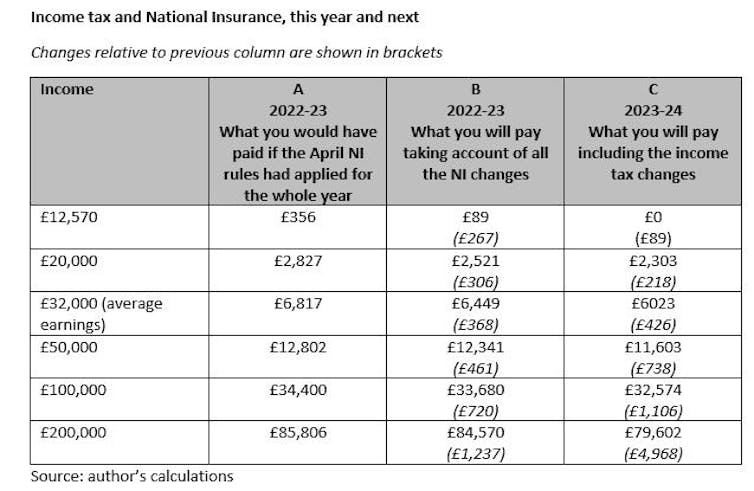

The government is giving big tax cuts to the better-off, but offering little to lower-income households. The recent 1.25% rise in national insurance is being reversed[16], and income tax will be cut in April 2023, with the basic rate falling to 19% (currently 20%) and the top 45% rate for the highest earners abolished.

As the table below shows, these changes mean take-home pay for someone on average earnings of around £32,000[17] will increase by £368 this year and then go up by another £426 next year. The poorest households, earning too little to pay NI or income tax, do not benefit at all.

But this support comes alongside new oil and gas licenses and an end to the ban on fracking. Neither of these strategies are likely to have a significant impact on energy prices, particularly in the short term, as is sorely needed. There are also serious questions about their compatibility with our climate change targets.

The plan includes an increase in the estimated revenue from the windfall tax on oil and gas, from £5 billion to £7.7 billion in this financial year. This tax could have been extended further to help pay for the energy price cap, and to boost investment in low carbon infrastructure.

Business impact

Steven McCabe, Associate Professor, Institute for Design, Economic Acceleration & Sustainability (IDEAS), Birmingham City University

Kwarteng’s decision to scrap the planned increase in corporation tax, which had been due to rise from 19% to 25%, will be welcomed by businesses. As the chancellor claimed, this should make the UK a more attractive place to invest and result in a jobs and tax-take increase. It also means investors in companies retain more profits.

Whether this provides sufficient incentive for additional investment is questionable, however. On the other hand, a removal of the cap on fees for certain specialised investment schemes may encourage more funds for innovation and product development.

Kwarteng intends to underpin growth through 40 investment zones throughout England that will offer special tax breaks and reduced planning and environmental regulation for business. Kwarteng claims this will “unleash the power of the private sector”.

We’ve seen this sort of intervention before in the 1980s and again in 2012, with mixed results. Kwarteng’s investment zones are also unlikely to solve the huge social and economic problems we face.

Rather than Boris Johnson’s fabled objective of “levelling up”, they risk merely encouraging existing businesses to relocate to enjoy tax breaks. This will not recreate the thousands of well-paid manufacturing jobs lost when traditional industries closed in the 1980s.

Overall, many businesses will be disappointed by what was announced. There will be continued concerns about business closures and redundancies accelerating, with the consequential loss of much-needed tax revenue to pay off the ever-increasing public debt.

What businesses needed from the government was genuinely radical intervention to stimulate manufacturing. What we got will not produce the growth we need. Look at the immediate market reaction, as measured by the falling pound.

Property market

Jean-Philippe Serbera, Senior Lecturer in Banking And Financial Markets, Sheffield Hallam University

A permanent reduction in stamp duty, at a time when the property market has rarely been so strong, is perhaps one of the stranger aspects of the mini-budget. Kwarteng has raised the threshold for payment from £300,000 to £425,000 for first time buyers and to £250,000 for all other residential purchases.

The motive behind the change must be to further support the housing market by reducing overall costs for those trying to get onto the housing ladder, while also benefiting property investors.

On the face of it though, it seems ill-timed. Property prices are already at record levels, and it will cost the government billions of pounds. However, with the Bank of England raising interest rates, and inflation squeezing personal savings, it may be a way for the government to temporarily postpone a crash in UK house prices that is bound to happen – and sooner rather than later.

References

- ^ biggest package of tax cuts (twitter.com)

- ^ anticipated (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ cost of living crisis (yougov.co.uk)

- ^ Kwarteng’s plan (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ consumer (www.bbc.co.uk)

- ^ business (www.iod.com)

- ^ regional investment zones (businessnewswales.com)

- ^ public borrowing (www.investmentweek.co.uk)

- ^ not guarantee (www.centreforcities.org)

- ^ Anthony Barber (www.ruffer.co.uk)

- ^ to go cap in hand (www.nationalarchives.gov.uk)

- ^ record trade deficit (www.cityam.com)

- ^ recently dropping (bmmagazine.co.uk)

- ^ raising interest rates (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ “trickle down” (www.imf.org)

- ^ reversed (www.gov.uk)

- ^ around £32,000 (www.ons.gov.uk)

- ^ recent research (eprints.lse.ac.uk)

- ^ much higher in the UK (www.ons.gov.uk)

- ^ another 0.5% (www.bankofengland.co.uk)

- ^ variable-rate or tracker mortgage (www.ukfinance.org.uk)

- ^ unsustainable (ifs.org.uk)

- ^ £1,000 cut (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ £1,400 worse off (jpit.uk)

- ^ Joe Biden declared (www.itv.com)

- ^ Bankers bonus cap: why scrapping it could hurt the UK economy (theconversation.com)

- ^ twice the levels (www.ofgem.gov.uk)

- ^ social tariff (www.nea.org.uk)

- ^ fuel poverty (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ health (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ financial wellbeing (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ popular approach (www.ft.com)

- ^ growth plan (www.gov.uk)

- ^ Shutterstock/David Falconer (www.shutterstock.com)