Tory tax plans need to be more strategic to tackle the cost of living crisis – here’s why

- Written by Tolu Olarewaju, Economist and Lecturer in Management, Keele University

The cost of living crisis is a key issue[1] for the Conservative leadership candidates hoping to become the next prime minister of the UK. But the taxation strategies suggested by the final two Conservative party leadership hopefuls, Rishi Sunak and Liz Truss, won’t solve this problem.

Instead, we need a more nuanced approach that will support all UK households, but particularly those in more deprived areas who have been hit hardest by rising bills and slowing economic growth. Understanding how and why inflation has affected these households is an important step in assessing the solutions the candidates have put forward.

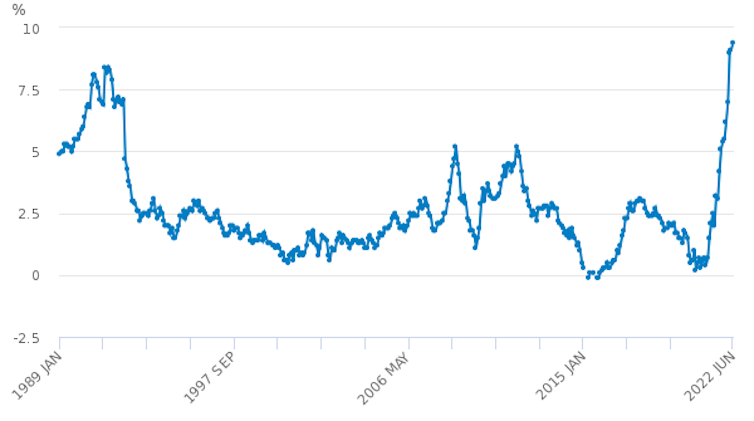

UK inflation rate

One of the main contributors to the UK’s current economic situation is that the high rate of inflation – 9.4% as of June 2022[2] – has outstripped wage and benefit increases. Although UK unemployment[3] held at 3.8% from March to May 2022, real disposable incomes (pay adjusted for inflation and after taxes and benefits) fell by a record[4] 2.8% during the same period.

This means work is becoming less effective at warding off poverty[5], particularly in areas of the UK where incomes and investment are lower; where infrastructure needs updating and where overall economic prospects are more bleak than for the rest of the country. The situation has been further intensified by tax increases, with 2021 seeing the largest rise in taxes[6] (as a share of national income) of any year since 1993.

The last-remaining Tories vying to become Conservative party leader and prime minister will engage in a head-to-head debate in Stoke-on-Trent on July 25. As an economist working on poverty reduction[7] and living in Stoke-on-Trent – one of the most deprived[8] parts of the UK – I see the effects of the cost of living crisis every day. The tax strategies put forward by Sunak and Truss will have major implications for the areas of the UK most affected by the rising cost of living.

Liz Truss

The foreign secretary’s tax strategy indicates she sees UK inflation as “cost-pushed”, which means there is a reduced supply of goods and services. With this kind of inflation, prices are pushed up by rising costs of production and raw materials.

The current inflation situation in the UK has arisen partly due to supply chain issues as businesses struggled to meet[9] a boom in demand following the pandemic. Higher oil prices[10], as a result of the war in Ukraine, have not helped the situation.

Truss has also blamed[11] UK inflation on the Bank of England increasing money supply. In addition to setting a money supply target, Truss wants to focus on boosting the supply-side of production. Her pledge to reduce both personal and corporate taxes via a £30 billion tax cut package has been criticised as inflationary[12] by Sunak. She has not yet provided the exact details[13] of the plan, however.

Rishi Sunak

On the other hand, the former chancellor’s economic strategy suggestions are designed to address demand-pull inflation. This kind of inflation occurs when there is too much demand for the limited goods and services being produced. This causes prices to go up, resulting in inflation. This excessive demand can also be described as as too much money chasing too few goods.

Sunak intends to stick with his plan from his days as chancellor to increase both National Insurance[14] and corporation income tax. This will mean raising[15] corporation tax from 19% to 25% next spring, while offering investment relief to firms. He has also pledged[16] a 1p cut from the 20p basic rate of income tax in April 2024.

The ex-chancellor has been criticised for the current government’s loose monetary policy[17] contributing to the UK’s high inflation. Before launching his campaign, however, the chancellor announced a multi-billion-pound package of support that he said would have a “minimal impact[18]” in terms of further increasing inflation.

How to help ‘left behind’ areas

The cost of living crisis displays elements of both types of inflation. Difficulties in getting materials needed for production of goods, higher wages and price increases for energy and agricultural commodities, are all signs of cost-push inflation. And demand-pull inflation has resulted from increased government spending[19] during the COVID crisis and greater spending by households due to savings made[20] during the pandemic.

Cost-push inflation cannot be solved by higher taxes for households, as proposed by Sunak, especially as most of the inflation in this case is imported[21], for example through higher energy prices. More taxation in this case will only hurt households already struggling with costs. On the other hand, Truss’ plan to reduce taxes indiscriminately may worsen inflation.

Deprivation levels in Stoke-on-Trent

This is particularly true for England’s “left behind[22]” neighbourhoods. These areas[23] – predominantly in post-industrial and coastal parts of England – have been acutely affected[24] by the cost of living crisis. More than a quarter (26.7%) of people living in left behind neighbourhoods are income deprived[25], compared to 12.9% in England as a whole.

A more nuanced approach to taxation is needed if we are to help these areas in particular. Tax cuts could ease the burden on households and small businesses that are struggling, alongside tax increases for large firms – particularly those that have recorded substantial profits[26] such as the energy sector[27].

The 25% windfall tax[28] imposed on oil and gas companies last May is a good example of how the next government can use taxes on businesses to support those who experience fuel poverty. This directly benefits left behind areas where fuel poverty[29] is an issue for 8.8% of people, compared to 2.3% in England as a whole.

Tax incentives for investments that benefit left behind areas should also be on the agenda of the incoming government. Cutting taxes for firms that actively invest in the UK economy would be a good start – especially those investing in left behind neighbourhoods. This could create better paying jobs and stimulate vital growth in these communities and across the country.

References

- ^ key issue (www.thetimes.co.uk)

- ^ 9.4% as of June 2022 (www.ons.gov.uk)

- ^ unemployment (www.ons.gov.uk)

- ^ record (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ warding off poverty (www.jrf.org.uk)

- ^ largest rise in taxes (www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk)

- ^ poverty reduction (www.researchgate.net)

- ^ most deprived (www.ons.gov.uk)

- ^ meet (www.bankofengland.co.uk)

- ^ oil prices (www.weforum.org)

- ^ blamed (www.itv.com)

- ^ criticised as inflationary (nation.cymru)

- ^ exact details (www.standard.co.uk)

- ^ National Insurance (www.express.co.uk)

- ^ raising (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ pledged (www.independent.co.uk)

- ^ monetary policy (www.thetimes.co.uk)

- ^ minimal impact (www.bloomberg.com)

- ^ increased government spending (commonslibrary.parliament.uk)

- ^ savings made (www.ons.gov.uk)

- ^ imported (www.economicsobservatory.com)

- ^ left behind (www.ons.gov.uk)

- ^ areas (ocsi.uk)

- ^ acutely affected (www.appg-leftbehindneighbourhoods.org.uk)

- ^ income deprived (www.ons.gov.uk)

- ^ substantial profits (tradingeconomics.com)

- ^ energy sector (www.marketwatch.com)

- ^ 25% windfall tax (www.reuters.com)

- ^ fuel poverty (www.gov.uk)