What to do with anti-maskers? Punishment has its place, but can also entrench resistance

- Written by Meg Elkins, Senior Lecturer with School of Economics, Finance and Marketing, RMIT University

What’s driving “Bunnings Karen” and others to film themselves arguing with shop assistants about face masks and human rights? And how should we respond?

Victorian premier Daniel Andrews has called their behaviour “appalling[1]” and advised us to ignore them, because “the more you engage in an argument with them, the more oxygen you are giving them”.

Others are taking a more confrontational approach.

On Australia’s morning television Today show, presenter Karl Stefanovic cut off an interview with an anti-masker[2] after telling her she had “weird, wacko beliefs” and “I can’t listen to you anymore”. And that’s relatively tame, compared with what’s being said about the “covidiots” on social media.

Our desire to condemn and punish non-cooperative behaviour is strong. One of the key insights from behavioural econonomics over the past few decades is that people are willing to punish others at a cost to themselves, and this helps increase cooperation – to an extent.

Read more: Can Australian businesses force customers to wear a mask? Here's what the law says[3]

But condemnation and punishment can also reinforce resistance among the uncooperative. We must also try to understand the complex emotional motivations of those refusing to wear masks.

Anti-masker motivations

It’s hard to say how many people are opposed to mandatory mask wearing. But the evidence suggests social media channels such as YouTube and Facebook have increased the popularity of conspiratorial theories that governments want people to wear masks as some form of mind control.

The COVID conspiracy movement is a broad church, but there appear to be two fundamental traits among its adherents.

First, a belief in their own intuitive ability to know the truth.

Second, a deep and cultivated distrust of government and other institutions. They do not believe the mainstream media, and there is no shortage of alternative media narratives to sustain them.

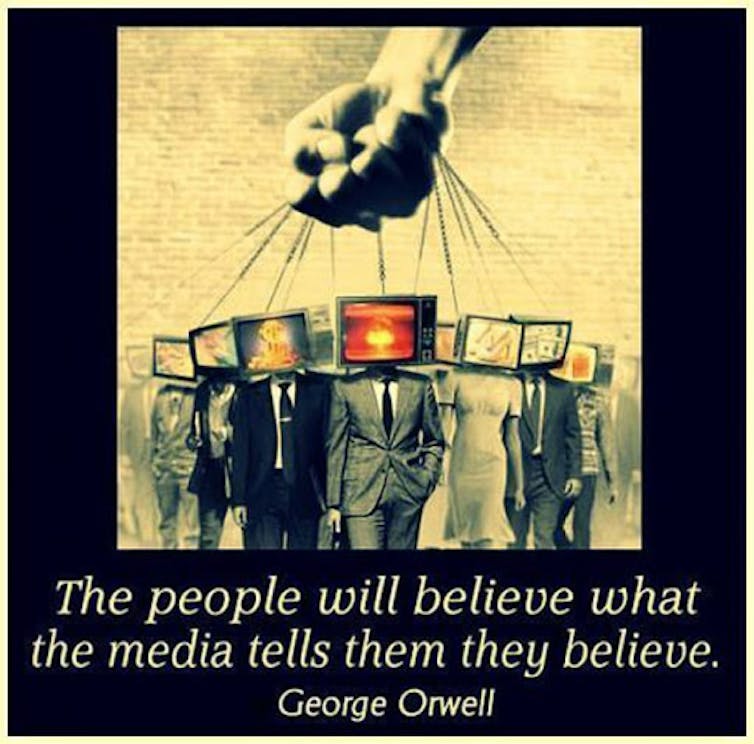

A popular conspiracy theorist meme. Ironically the quote from George Orwell is a fabrication.

A popular conspiracy theorist meme. Ironically the quote from George Orwell is a fabrication.

Trust or distrust in authority, and whether one is more obedient or rebellious, has been shown to be an innate tendency, shaped by experience and culture. It is very difficult to shift. As social psychologist Jonathan Haidt notes in his 2012 book The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion[4], our minds were designed for “groupish righteousness”:

“We are deeply intuitive creatures whose gut feelings drive our strategic reasoning. This makes it difficult – but not impossible – to connect with those who live in other matrices”

Distrust in authority is easily reinforced by any perceived mixed messages from official souces[5]. In the case of masks, health officials initially advised against wearing them. We know the main purpose of this message was to safeguard limited supplies for health workers, but the change in tune has helped entrench anti-masker beliefs the government isn’t truthful.

Cooperation and punishment

So what to do?

The important issue is not whether we can change anti-masker beliefs but whether we can change their behaviour.

Traditional economic theory, which assumes people are rational and follow their self interest, would emphasise carrots and sticks.

Behavioural economics, which understands that decisions are emotional, would also recognise that people are quite ready to take a hit just to express their disgust about being treated unfairly.

This has been repeatedly demonstrated by a staple experiment of behavioural research – the “ultimatum game”. It involves two players and a pot of money. One person (the proposer) gets to nominate how to split that money. The other (the responder) can accept or reject the offer. If it’s a rejection, neither gets any money.

A “rational” responder would accept any offer over nothing. But studies have consistently shown a large percentage opt for nothing when they consider the money split unfair.

This sense of fairness is a deep evolutionary trait shared with other primates. Experiments with capuchin monkeys[6], for example, have shown that two monkeys offered the same food (cucumber) will eat it. But if one monkey is given a sweeter treat (a grape) the other will reject the cucumber.

Other types of games show this innate sense of fairness leads to a desire to penalise “selfish” people in some way. Most of us are “conditional cooperators”, and punishment of non-cooperative behaviour is important to maintain than cooperation.

Read more: Coronavirus contact-tracing apps: most of us won’t cooperate unless everyone does[7]

But punitive measures may paradoxically reduce compliant behaviour.

Economists Uri Gneezy and Aldo Rustichini, for example, conducted an experiment in Israel[8] to discourage parents picking up their children from day care late by introducing fines. The result: lateness actually increased. Fines became a price, used by parents as a way to buy time.

Read more: To change coronavirus behaviours, think like a marketer[9]

Need to express dissent

If a rule jars with one’s beliefs, following it can cause huge emotional turmoil. Particularly if disobedience is the only way to express disagreement.

Could anti-maskers express their feelings in another way?

Economists Erte Xiao and Daniel Houser demonstrated this possibility in a variation of the standard ultimatum game[10].

Normally the game only allows responders to express their feelings through accepting or rejecting a proposer’s offer. Xiao and Houser allowed responders to express their feelings about an unfair offer by sending a simple message. The result: they became much more likely to accept an unfair offer.

Some enterprising types seem to have cottoned on to this idea by selling face masks enabling wearers to signal their conspiracy convictions.

So if we want to anti-maskers to cooperate, we will need to tolerate them expressing their dissent in other ways.

Ostracism and ridicule will just increase their resistance and resentment, and reinforce the “us versus them” mentality.

So if we want to anti-maskers to cooperate, we will need to tolerate them expressing their dissent in other ways.

Ostracism and ridicule will just increase their resistance and resentment, and reinforce the “us versus them” mentality.

References

- ^ appalling (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ with an anti-masker (www.youtube.com)

- ^ Can Australian businesses force customers to wear a mask? Here's what the law says (theconversation.com)

- ^ The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ from official souces (onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- ^ Experiments with capuchin monkeys (www.nature.com)

- ^ Coronavirus contact-tracing apps: most of us won’t cooperate unless everyone does (theconversation.com)

- ^ experiment in Israel (rady.ucsd.edu)

- ^ To change coronavirus behaviours, think like a marketer (theconversation.com)

- ^ in a variation of the standard ultimatum game (www.pnas.org)

Authors: Meg Elkins, Senior Lecturer with School of Economics, Finance and Marketing, RMIT University